Editor’s Letter

This spring, I set up a thirty-seven-gallon fish aquarium.

I’ve been raising fish for a while. I got goldfish for the mantel several years before grad school, and I’ve had a betta there since I got married over thirty years ago. Bettas generally live by themselves, so there isn’t much to learn about them—nor are they very active. They simply hang there most of the time looking gorgeous, and last for several years. I’ve named them all after athletes, with my current betta being a purple stunner named Brent Burns, a hockey player for the Carolina Hurricanes.

My daughter got a ten-gallon tank in high school and then left it behind when she went off to college. It was a rather murky, algae-filled tank, high schoolers being what they are, and I set about making it clean and comfortable for her remaining fish—mostly a variety of silvery tetras. When one would pass, I’d buy another, because we all need friends, right?

I grew very fond of the little guys, as one might guess from my background with fish, and eventually decided they needed a bigger home and more visibility than my daughter’s room tucked upstairs. It’s so peaceful and beautiful to watch them swim back and forth, seemingly floating in and around the plants and such. The new aquarium is in our bedroom and visible from the living room chair where I work from home.

It’s been a learning experience.

In reading up on aquarium care, I learned that new tanks needed to “cycle”—i.e., build up “good” bacteria before moving the fish in. I also studied up on the different types of fish, adding live plants, dealing with algae, the many versions of filters, the hows and whys of water changes, nursing a sick fish . . . and have practically earned a chemistry degree sorting out the chemicals one might or might not add (helpful hint: snails don’t like any additives other than slime coat, and if the package tells you it’s fine, it’s not).

All my fish are tetras, but there are hundreds of tetra types and I have five or six. Some look substantially different from the others, ranging from one to three inches and in black, silver, white, orange, and even neon red and blue, but I’ve always viewed them as kind of the same. They’re not really, though, and although they mingle well enough (the tetras at least—not all fish!), some require some of the same to form schools.

This transfer from tank to tank . . . it’s not as simple as plucking them from one and dropping them in the other. In addition to needing good bacteria, there are half a dozen other factors I test the water for regularly. Also, the temperature change. Who knows what else? Most of my larger fish, although several years old (they live to five at best), have made the transition. The neons and snails? Not so well. (Turns out, everything that says “safe” means safe for all but snails!)

I’m finally at the point where they’re all thriving, but it’s been traumatic. It’s heartbreaking and nerve-wracking to find a friend floating lifeless every other day. Even worse, I’ve learned that even friendly fish will eat a companion when it becomes ill. Bad enough to realize the count has gone down; worse to find pieces of a friend who’d been swimming happily not that long before. I was greatly depressed and considering giving up when the tide thankfully turned.

Not Quite a Vegetarian

Like many young people when they really start equating cows with beef and pork with pigs, I declared myself a vegetarian in high school. Unlike most, I still try to keep my meat eating to a minimum, although my rather carnivorous family has limited my success. (And I do believe in the circle of life, but we need to be responsible stewards of our place on this earth.) I have found a variety of tofu dishes they actually like, and we minimize the red meat in favor of chicken and fish.

All of this came crashing down on my bleeding little heart, though, the last (thankfully!) time I found a half-eaten fish in my tank. Unlike the previous victims, this one still had a spine and ribs. It still looked way too much like the little fish I loved and fed just hours before, and . . . way too much like my own dinners.

The Boxes We Build

So what does all this blabber about fish have to do with anything?

This may seem hard to believe but, even though I know so damn much about them, I’d never really equated the beloved floating pets in my various aquariums with the tasty and nutritious fish I’ve served. To those who don’t raise fish, that might sound silly, but it’s the kind of crazy mental gymnastics we do to make quick decisions, gloss over hypocrisies, and get through life.

Not all boxes are bad, and in some ways they’re a necessity. Indeed, one might view them as applied learning. We see or hear or experience something in the moment that we then extrapolate to a broader group amongst whom we see similarities. If we see BMWs driving rather recklessly, as one tends to in my neck of the woods, we eventually become more cautious (and perhaps a little irritated!) around them. It might be an unfair assessment of every BMW we pass, but it keeps us safe.

Sometimes, however, these boxes can conflict with each other. We see this a lot with political affiliations. The right will point out inconsistencies in leftist ideology (think, for example, about white feminists not supporting their Black sisters) and then call them hypocritical; conversely, the left will point out the hypocrisy of, say, supporting a fetus’s right to life but then not supporting them once they’re born. Again: mental gymnastics.

The same thing happens around “fact” vs. “opinion.” We convince ourselves that the things we want to believe are “facts,” often simply because our tribe says they’re so, while people with whom we disagree are merely expressing (erroneous) “opinions.” I remember when the neighbor of a friend posted something on Facebook that was, well, ludicrous to me. I pointed out, as nicely as I was able, that it wasn’t actually true and included a link to Snopes. Her reply? That it didn’t matter if it were true or not—it was plausible enough that it could be true.

The Bigger the Box

To all but the most dedicated vegetarian, the inconsistencies in my relationships with fish are quite trivial—perhaps even amusing. My friends are certainly amused by my views of BMWs, especially given the way I drive (uneasy grin). When we get to political views or fact vs. fiction, the need for a more consistent worldview becomes much more important.

Far worse, even, is when we put people in boxes—and worse still when these boxes are used to hurt the inhabitants. You might remember when the body of Alan Kurdi, a two-year-old Syrian refugee, washed up onto the beach in Turkey, Americans were horrified and outraged. Less than five years later, when almost-two-year-old Angie Valeria washed up on the shores of the Rio Grande with her father, many Americans simply said, “they had it coming; it was illegal immigration.” The situations couldn’t have been more similar, but people put them in different “boxes” based primarily on their countries of origin.

Now? Texas has put barbed wire in the Rio Grande to deliberately hurt those who’d attempt to cross. Their box is officially “less than people.”

Little Pink Houses

Hopefully you’ve made the connection by now to racism, racial equity, and racial equality.

Far too often you’ve heard (or, if you’re white, caught yourself saying) something with an implicit “for a Black person” at the end of the sentence. “You’re so smart (for a Black person)!” “You’re so articulate (for a Black person)!” “You’re so well dressed (for a Black person)!” It’s also the basis for telling that one Black friend or coworker, “You’re not like other Black people!” Of course they are; they’re simply not like the speaker’s idea of what Black people are–the invisible box that defines them.

As with poor little Angie Valeria, white people have different expectations for folks in the People of Color box than they do for other white folks. When a couple of different teens I knew were caught with illegal drugs, lawyers were arranged, lessons were learned, records were expunged (because they’re kids! No need to ruin their future!). But when Philando Castile was stopped for a taillight and might or might not have been high, it was appropriate to shoot him dead? Similarly, Michael Brown.

Even when white folks are sympathetic, it’s a seven out of ten at best. When Dylann Roof killed a room full of Black parishioners, sure, we were sad, but we didn’t weep and wail and call out en masse for an end to white supremacy. When George Floyd was murdered, white people finally marched but they couldn’t be bothered to investigate the systemic racism in our justice system. What happened to George was wrong, but to some it wasn’t as wrong as the murder of a white person. Even when we white folks think we’re responding sympathetically, it’s subdued.

Of course, these boxes are as old as enslavement. We didn’t allow Black people to be educated, then labeled them intellectually inferior. We bound them and beat them, then said they couldn't be trusted when they tried to run away. We sold their children and now we accuse them of not being responsible to their families. If someone did any of these things to white folks, we’d immediately be appalled.

Even as these less-than boxes continue, we’re creating new ones as fast as we can. Progressives, socialists, woke people, fascists, climate deniers . . . the list is long and ever growing, and we add them to another less-than box, unable to learn any lessons from our racism.

The next time a Person of Color, an immigrant, a gay person, a woman is mistreated or upset, pause to think about your reaction. Would you be more likely to believe them if they were white / straight / male? Do you look for reasons to blame the victim? Is your sorrow somehow less than? And if so, why?

The truth is, like my fish and my fish dinners, we all create boxes and they often collide. We are complicated, messy, and inconsistent beings. But these boxes we so easily and unconsciously put people in are dangerous and frequently lethal. We have to develop the moral fortitude to interrogate our reactions, expose the contradictions, and treat all people as . . . people.

Love one another.

Sherry Kappel

OHF Weekly Managing Editor

New This Week

When My Best Friend Was White

Thinking back, there were a few times when my best friend(s) were white. I grew up in Minneapolis, whose population was no greater than fifteen percent Black. The block I grew up on had a dozen kids close in age, most of them white.

During the summer, I burst out the back door at 9:00 a.m. every morning and ran down the alley to go to Lyle’s house. Lyle had a basketball hoop attached to his garage, he owned a soccer ball, whiffle ball, and plastic bat, and his mother always served Kool-Aid when it got hot. When it rained, we played baseball with Topps baseball cards and a deck that described every activity (fly out, ground out, double, home run, etc). I would compile statistics at home at night, keeping up with batting averages, earned run averages, and league leaders in home runs.

Lyle, Mark, and Danny were my best friends from first through sixth grade, though I also had Black friends, mainly from the church I attended across town. It wasn’t uncommon for Black people to come from all parts of town and the suburbs to head to the Black parts of town to attend church on Sunday and then head back to their integrated neighborhood. Lyle, Mark, and Danny didn’t attend Field Elementary, a predominantly white public school, like I did. They all went to different private schools. I didn’t give it a thought at the time.

We became distant as time went on. I went to high school across town, taking the city bus. I got involved in athletics and spent much of my time outside of school looking for a pickup game of basketball or playing the board game Risk with some new friends from school. Danny moved out of town and I barely saw Mark and Lyle, even during the summers. These relationships lasted as long as they did because of proximity, similar interests, and the willingness to work through problems. Lyle was the least athletic in our group but owned most of the equipment needed to play games. Sometimes, he literally took his toys and went home, but we worked through the ups and downs to achieve goals because we genuinely liked each other.

Read the complete article at OHF Weekly.

The Conquistador Smackdown!

Here’s a fact about misinformation, fake facts, and biased messaging: many of us have been dealing with folks talking in “absolute” truths, expecting they will be believed with no question or rebuttal, for generations. It’s dominant class status maintenance. Or better known as putting Black (and other oppressed) people in our place. The assumed right to define reality for others is a line that has been etched in concrete long ago.

To not abide by this ordering of society invites backlash and aggression. Or worse. If you’re a Star Wars fan it’s the equivalent of living with millions of folks acting like they’re Obi-Wan Kenobi spewing assertions, retorts, and directions with a resolute belief that “the force” is with them. Whatever they say is truth, without question.

The Power of Messages

The power of defining others is described by Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folks, and characterized for Black people as living beneath “the veil” — the veil being a belief that maybe they (white people) are right. Maybe they are superior. Maybe we are less than they. That is a burden that haunts Black people. Doubt and insecurity becoming vulnerabilities within already needed armor.

About ten years ago, I visited the Museo Nacional de Colombia in Bogota. A really great place to learn some of the country’s history. One exhibit, drawings depicting Spanish conquistadors bearing gifts in full regalia greeting tribal royalty, took me by surprise. Underneath the images, they told of how the Spaniards thought they’d be greeting animal-like creatures with tails and limited intellect. I was impressed by the exhibition’s candor.

Read the complete article at OHF Weekly.

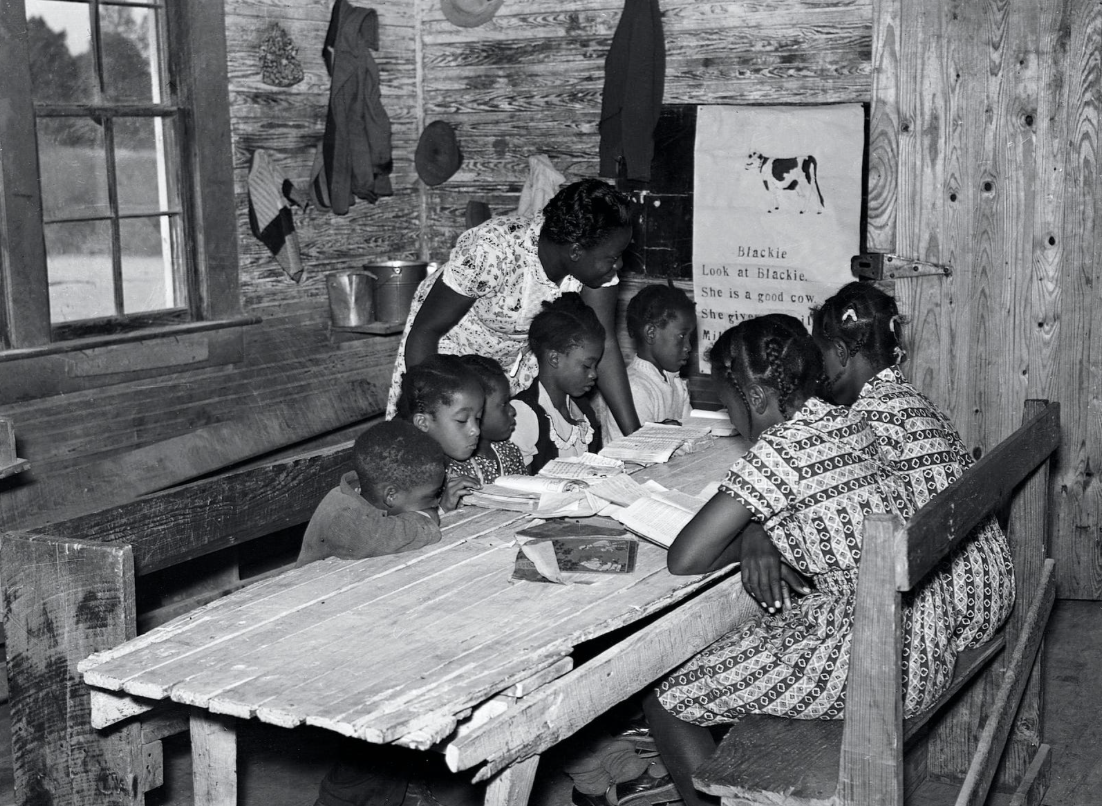

Lessons from Black Teachers of the Civil Rights Era

My grandmother’s name was Mrs. Zola Jackson.

As one of the handful of Black teachers in Mississippi during the Jim Crow era of racially segregated public schools, she faced a daunting challenge in providing a first-class education to students considered second-class citizens.

Educated at Rust College, a historically Black school, in the 1940s, she taught in the small city of Hattiesburg for over thirty years from 1943–1975, the majority of which was spent in elementary classrooms at DePriest, the school for Black children.

Before the 1954 landmark Brown v. Board decision that deemed segregated schools “separate and unequal,” the efforts of Black teachers went unheralded, underappreciated, and virtually unknown.

I, too, was disconnected from their stories until I became a public school teacher teacher myself and began my research on the oral histories of Black female teachers in Mississippi during the civil rights era.

My research revealed at least one important lesson: What Black teachers face today is not that different from what we faced in the past.

Read the complete article at OHF Weekly.

Support Our Human Family

Please give. We cannot do the work of racial equity without the support of people like you. In the same way that it takes a village to raise a child, it will take all of us to end racism and create a more equitable world. Racism does just harm its victims; it harms its perpetrators and bystanders. Racism harms everyone.

Your tax-deductible donations will help us continue our anti-racism work. No donation is too small, be it one time or monthly. Thank you for your support.

Final Thoughts