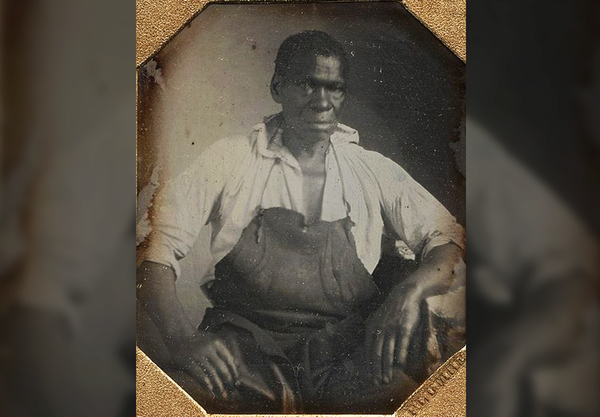

My personal feelings about celebrating Juneteenth have shifted a few times. I first learned of Juneteenth long after my college years. A friend from Texas suggested a few of us in Orlando, Florida, join her in celebrating Juneteenth, which was a big thing in her home of Beaumont. Juneteenth, June 19, 1865, was the day enslaved people in Texas learned of their freedom. I understood why that would be a big deal in Texas. But why should people not from Texas be concerned?

Over time, Juneteenth became more popular throughout America—the concept of celebrating the end of enslavement, despite the span of time between when the Civil War is considered to have ended, April 9, 1865, and Juneteenth, seventy-one days later. I eventually got curious and started digging into what happened during those seventy-one days?

I first thought there might have been a delay in communication. What forms of information transmission were available those days such that an event as important as the Civil War ending got missed for almost two-and-a-half months? There was the mail, which was slow and unreliable. Newspapers were available, although a large percentage of the population, especially the enslaved population, was illiterate (not by choice). Telegraph depended on cables physically connected between cities, but Texas wasn’t excluded from the telegraph and should have received the news.

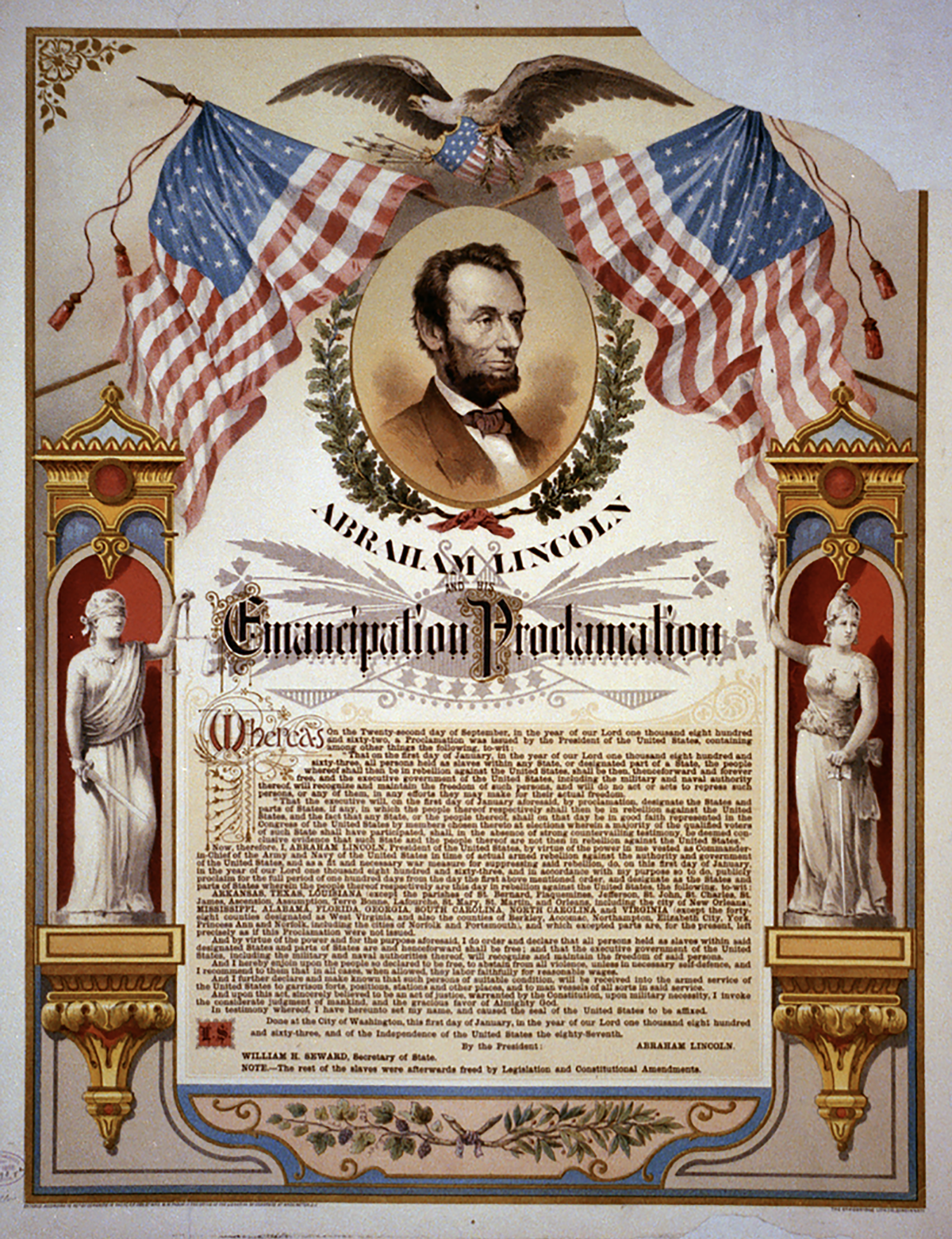

People were the other source of information. Refugees from battleground states steadily streamed to Texas. They included plantation owners and farmers who brought enslaved people with them. Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment outlawing slavery on January 31, 1865, and was headed towards ratification by the end of the year. The people who traveled to Texas by train, boat, and other means knew the war was over, and still, the Texas enslaved people were not freed. Why?

The answer appears to have involved cotton. Planting season in Texas runs from mid-May to mid-June, and if the enslaved people were released right when the Civil War ended, white farmers would have lost an entire year’s worth of crops. Enslaved people in Texas should have been freed two-and-a-half years before Juneteenth via the Emancipation Proclamation as in other rebelling southern states. Without the ongoing presence and forced compliance of the Union army, Texans had no incentive to fall in line with the decree. Like the enslaved people in every other state that seceded from the Union, they would have had to reach Union territory to actually be free and Texas was a long way from the nearest free state. After the war ended, over two thousand Union troops gathered over time in Galveston, Texas, and waited for Major General Gordon Granger to arrive and announce the freeing the enslaved people of Texas:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

—Major General Gordon Granger, General Order No. 3

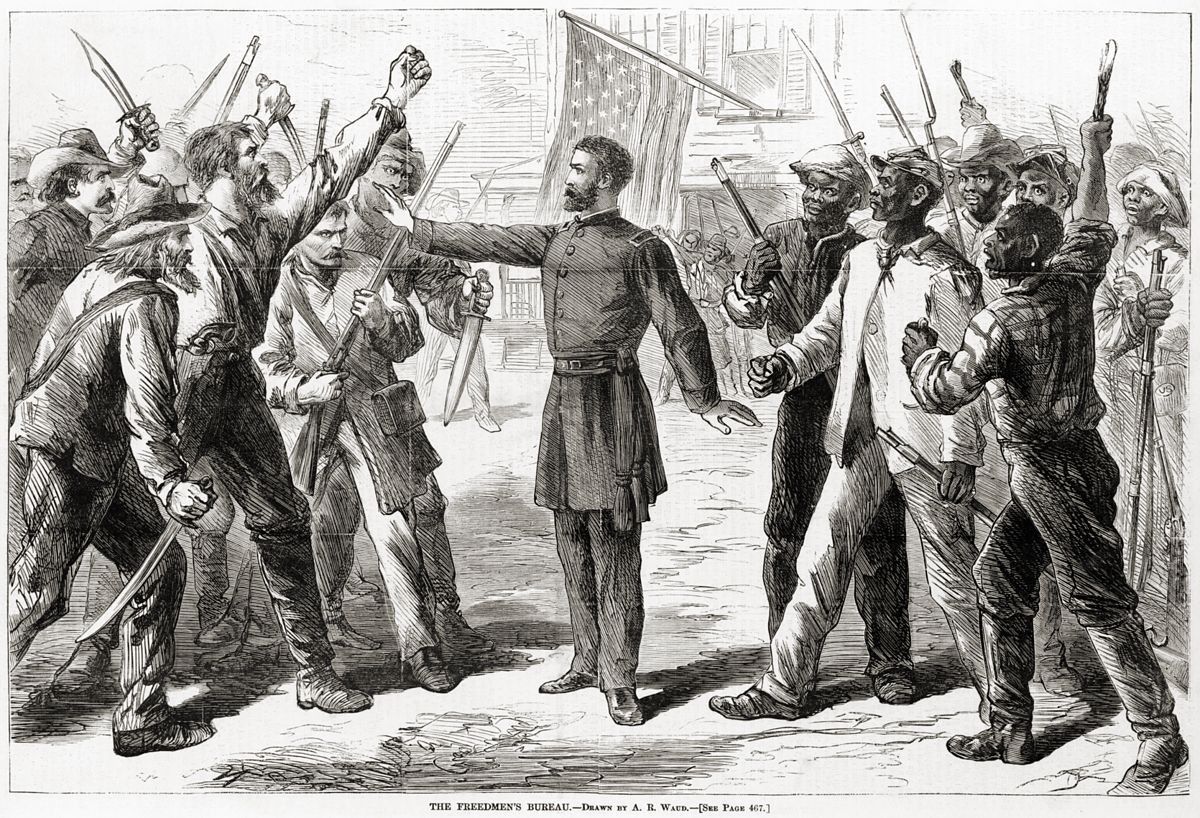

The wording of his announcement is somewhat vague. It tells enslaved people to stay right where they are, continue working for the same people who enslaved them. But they are now employees instead of enslaved people though there is no provision compelling the landowners to pay them any amount, let alone a standard or minimum wage. The statement says not to go to military posts or look for any support of any kind. It may be grammatically incorrect but what they were saying is, “We don’t got you!”

Was the freedom promised after the war truly freedom? The state of Texas (like every other Confederate state) got to work creating their Black Codes, which came as close as they could to reinstating the enslavement of Black families. The Texas legislature passed a massive bill in 1866 that included some of the following provisions:

“Persons of color shall not testify, except where the prosecution is against a person who is a person of color; or where the offence is charged to have been committed against the person or property of a person of color.”

“Every laborer shall have full and perfect liberty to choose his or her employer, but when once chosen, they shall not be allowed to leave their place of employment, until the fulfillment of their contract, unless by consent of their employer, or on account of harsh treatment or breach of contract on the part of the employer, and if they do so leave without cause or permission, they shall forfeit all wages earned to the time of abandonment.”

“All labor contracts shall be made with the heads of families; they shall embrace the labor of all the members of the family named therein, able to work, and shall be binding on all minors of said families.”

“Wages due, under labor contracts, shall be a lien upon one-half of the crops, second only to liens for rent, and not more than one-half of the crops shall be removed from the plantation until such wages are fully paid.”

“In case of sickness of the laborer, wages for the time lost shall be deducted, and, when the sickness is feigned, for purposes of idleness and also, on refusal to work according to contract, double the amount of wages shall be deducted for the time lost and, also, when rations have been furnished, and should the refusal to work continue beyond three days, the offender shall be reported to a Justice of the Peace or Mayor of a town or city and shall be forced to labor on roads, streets and other public works, without pay, until the offender consents to return to his labor.”

“Laborers, in the various duties of the household, and in all the domestic duties of the family, shall, at all hours of the day or night, and on all days of the week, promptly answer all calls, and obey and execute all lawful orders and commands of the family, in whose service they are employed, unless otherwise stipulated in the contract; and any failure or refusal by the laborer to obey, as herein provided, except in case of sickness, shall be deemed disobedience, within the meaning of this Act. And it is the duty of this class of laborers to be especially civil and polite to their employer, his family, and guests, and they shall receive gentle and kind treatment.”

Slavery only technically ended in Texas on Juneteenth. The Texas of the past chose not to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment until 1870, which was a condition of regaining Union statehood. Texas then passed the Texas Constitution of 1876—which has been amended many times throughout the years but still retains much of the same tenor as before. When modern-day politicians speak of “purity of the ballot box,” they are using the same language as in 1876 which disenfranchised Black voted. In other words, the Texas of the present is simply doing what it has always done: making it harder for minorities to vote. They’ve even rewritten history in their schoolbooks to make all they’ve done seem palatable.

I can’t celebrate Juneteenth because I see it as nothing to celebrate. Enslaved people, for the most part, stayed right where they were, doing the same things, and were required by law to be civil to their white “employers.” Instead of celebrating Juneteenth, we ought to be talking about how to make things right in Texas and every state that passed Black Codes which undermined what hundreds of thousands of people, white and Black, died for. If someone has a better idea, I’m all ears, but I’m thinking reparations.

Reparations: The making of amends for a wrong one has done by paying money to or otherwise helping those who have been wronged.

I used to be against reparations. More so against protesting or fighting for reparations because I thought they would never happen. That was before I discovered the heinous acts perpetrated against Black people, whether it was enslavement or all the rules that governed the faux freedom that were the Black Codes, later Jim Crow, and currently mass incarceration, voter suppression, and income inequality.

The middle class was created in huge part due to the G.I. Bill that provided 100 percent financing to veterans of World War II that almost no Black veterans received. Throw in the fact that Black people couldn’t get FHA financing either, plus the effects of redlining, steering, and blockbusting. I’ve begun to believe that reparations are not only feasible but reasonable and deserved, as well.

Do you know who did receive reparations in America? You might think I’m about to point out the Japanese who received $1.6 billion for the eighty thousand or so survivors of the internment camps that housed Japanese Americans between 1942–1945. They did get reparations, but I’m not mad at them. At about $20 thousand per survivor, they didn’t get enough. The others who got reparations? White people. Those who lost their enslaved people at the end of the Civil War, even though many were returned under the Black Codes and Jim Crow, and the type of sharecropping that Texas instituted after Juneteenth.

After the Civil War, General William T. Sherman issued Special Field Order 15 to give recently freed enslaved Black Americans up to forty acres of land to get them on their feet and keep them from being dependent on the Union Army. This order led to the claim that Black people were to receive “forty acres and a mule.” The perception is that Black people never got their land and work animals. In truth, over four hundred thousand acres of land were redistributed to freedmen in South Carolina in forty-acre plots. A later order he issued called for loaning a mule to the Black farmers. Some white Unionists who helped the Union effort during the war also received plots of land.

The Black and white farmers tilled and improved the land, some of which took considerable work to raise food crops. These farmers began receiving land in 1861. When Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s segregationist running mate, succeeded him. Johnson immediately superseded Field Order #15 and returned the land to the previous white owners, in better condition than they left it.

Juneteenth is one situation of many in America’s past that cry out for reparations. It appears that the Union army, along with Texas farmers, conspired to keep the news from enslaved people to keep them working in the fields. Legislatures in Texas and other states instituted laws to keep Black people enslaved. While it was mandated that white “employers” pay their “employees” wages, Black people had a curfew that didn’t apply to their white counterparts. Like current Florida law, where as few as three people gathering in protest can be considered a felony and arrested, Black people gathering except for church could get them arrested with the penalty being sent to white people’s fields.

So, have your cookouts, throw block parties, dance and shout over the fact that Black people were told they were free seventy-one days after the fact and arguably haven’t achieved full freedom in Texas yet. Juneteenth is now celebrated in forty-eight states; Hawaii and South Dakota took a pass. Some corporations even give their employees the day off. As for me, I’m going to sit this one out. I don’t see cause to rejoice.

Updated: Sunday, June 20, 2021